Migrants’ Cash Keeps Flowing Home

By MIRIAM JORDAN

Migrant workers abroad sent more money to their families in the developing world last year than in 2010, and they are expected to transfer even more cash home this year despite the economic uncertainty gripping the globe.

The U.S. leads the world as the biggest source country for remittances, much of it sent home by the millions of Latin Americans working in the country.

Associated Press

Technological advances have facilitated and lowered the cost of sending money.

All told, the world’s 215 million international migrants transferred about $372 billion to developing countries in 2011 compared with $332 billion in 2010, according to the World Bank. The bank projects remittances will reach $399 billion this year and $467 billion by 2014.

For some time now, remittances have played a key role in supporting families and stabilizing the economy of developing countries. Their quick recovery after a temporary dip in 2008 and 2009 has been buffering many countries from potentially devastating effects of the global slump.

Despite the weak U.S. job market, tighter immigration enforcement and violence at the border that have slowed migrant arrivals, central banks in Latin America reported brisk growth in remittances this year. Mexico reported a 5% increase—mostly from the U.S.—to $13.7 billion for the first seven months of 2012. Salvadorans sent $2.6 billion home from January through August, up 7% from the same period last year, according to the central bank of El Salvador. Guatemalan expatriates’ remittances, which account for 12% of their country’s gross domestic product, also are up this year.

The Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington-based think tank, predicts a 7% or 8% increase in remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean this year. The region received $69 billion in transfers in 2011, up from $64 billion in 2010.

Manuel Orozco, the Inter-American Dialogue’s remittance director, said several factors are keeping remittance flows especially strong to Mexico, home of the most migrants to the U.S. Washington has been issuing a record number of seasonal work visas for the U.S.: The tally nearly reached 270,000 in 2011, up from 144,000 in 2006.

Educated women are boosting remittances. About one-third of Mexican women working in the U.S. have a college degree or some higher education, and their ranks have been growing. “They send more money than anybody,” Mr. Orozco said.

In addition, immigrants who have been in the U.S. for several years are increasingly sending money to their home countries for purposes such as building houses, participating in business ventures or helping community organizations. So-called transnationally engaged migrants comprise only 8% of the total, but they send 10% more money than others, on average, according to Mr. Orozco.

Remittances remain a key source of hard currency for developing countries, often outstripping foreign direct investment and foreign aid. A recently published World Bank book, “Migration and Remittances during the Global Financial Crisis and Beyond,” said countries like Indonesia, India and Mexico were somewhat immunized from the global downturn by the influx of cash transfers from their nationals working abroad.

From 2008 to 2009, global remittances slipped 6%, far less than the double-digit slide in foreign direct investment during that period to countries such as India, Indonesia and the Philippines.

“There was an expectation that remittances would fall because of the crisis in countries where migrants work,” said Dilip Ratha, a World Bank economist who co-edited the book. “But after dropping during the peak of the crisis in 2009, remittances have not only bounced back—they are at a higher level.”

He said many migrants absorbed the setback of lower wages or irregular employment in recent years by cutting consumption, splitting lodging costs and making other sacrifices to keep money flowing back home. Remittances help feed, house and clothe families, as well as pay for schooling and other expenditures.

Day laborer Antonio Chavez of El Salvador, who lives in Silver Spring, Md., said he has managed to send his mother money, even when work was scarce during the recession. “I make sure she can pay her bills and buy medicine,” said Mr. Chavez, 49 years old. “I’m a carpenter, but I am willing to do any job in construction or landscaping.”

Technological advances, such as online transfers with a mobile device, have facilitated and lowered the cost of sending money. Wells Fargo & Co., which transferred $1.8 billion in remittances in 2011, lets its account-holders send money in person, by phone or online through its remittance service. Xoom Corp., an online money-transfer firm, sent more than $1.7 billion to 30 countries last year.

Migrants also are tapping technology to compare exchange rates and fees at different remittance companies. “Migrants know down to the penny a currency’s value, and they find the company giving the best exchange rate, fee and service,” said Eugenio Nigro, Xoom’s vice president of business development.

Intraregional remittances also are on the rise. Migrants are sending money from Russia to former Soviet states, like Tajikistan; from Italy to Albania; and from Brazil to its South American neighbors. “Because of its strong economy, Brazil is becoming a huge outbound market to Argentina, Peru and other countries in the region,” Mr. Nigro said.

Of course, remittances could become vulnerable to economic, political and regulatory changes in countries where migrants work. Also, volatile exchange rates and uncertainty about oil prices could have an adverse effect. And persistent unemployment in Europe may worsen migrants’ job prospects and harden attitudes toward migrants, creating political pressure to curb immigration.

In the U.S., a new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau rule designed to standardize the remittance industry as well as promote transparency and disclosure could raise costs for consumers when it goes into effect early next year, some experts said.

Daniel Ayala, head of global remittance services at Wells Fargo, praised the rule for creating a level playing field. But he cautioned that, “there are details that could…ultimately result in limiting access, higher costs and confusion.”

Write to Miriam Jordan at miriam.jordan@wsj.com

A version of this article appeared September 24, 2012, on page A16 in the U.S. edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: Migrants’ Cash Keeps Flowing Home.

http://online.wsj.com/article_email/SB10000872396390443995604578004280591669350-lMyQjAxMTAyMDIwNDAyODQ3Wj.html

View all posts in Anisya Blog

Posted on 24 Sep 2012

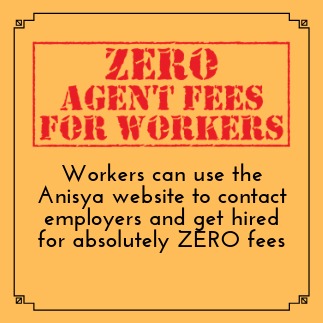

Help FDWs avoid debt

Anisya can help with the MOM paperwork

Found a suitable worker on Anisya? We can help with the MOM paperwork. Our service fee is $450. Click here for more info.

Full service hiring available

Need to hire an FDW in a hurry? Let Anisya help you with screening, short-listing and scheduling interviews with workers, and managing all the MOM paperwork formalities! More details here.

Anisya Web Services works in partnership with Anisya LLP (MOM License 12C5866) for MOM related transactions.

Anisya is a proud Social Enterprise member of the Singapore Centre for Social Enterprise (raiSE) and the Business For Good community which promotes the use of business for social impact.

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.