Meet-the-people sessions shouldn’t just be about personal grouses: Jolovan Wham

Original article at http://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/meet-the-people-sessions/2883470.html

HOME Executive Director Jolovan Wham speaks to 938LIVE’s Bharati Jagdish about what’s needed to make Singaporeans and the Government do more to improve the lives of migrant workers, and the need for Singaporeans to care about issues beyond just the personal.

Posted 18 Jun 2016 12:10

SINGAPORE: As Executive Director of the Humanitarian Organisation of Migration Economics (HOME), Mr Jolovan Wham has been at the forefront in trying to shape discourse on the treatment of foreign workers in Singapore.

His advocacy has also gone beyond the rights of guest workers, and he has in recent years turned his eye to issues such as the freedom of speech and expression. His approach has at times been controversial.

Mr Wham went “On the Record” with 938LIVE’s Bharati Jagdish about what’s needed to make Singaporeans and the Government do more to improve the lives of migrant workers, and the need for Singaporeans to care about issues beyond just the personal.

They started talking about his growing up sharing a room with his family’s foreign domestic helper.

Jolovan Wham: I was very young then, still very unaware of all these things. It was only when I got much older, that I realised what an awful situation it might have been for her. She had no privacy. I can imagine her having this conversation with me if she was really honest. “Can you just shut up? Can you not interrupt me? Can you not get in my way? I want to sleep. Can you just stay quiet and stay in a corner.” I can imagine her saying all these things.

Bharati: She didn’t of course.

Wham: She didn’t. When I saw that she lived and worked with us 24/7, I looked at my situation. I didn’t want to go to school every day, right? Why would I expect our live-in domestic worker to want to work for us every day? I don’t want to see my teachers every day, but my domestic worker is doing exactly that – she’s facing her bosses every day. It was just empathy. It was just putting myself in her shoes. If I didn’t want this for myself, why did I think that this woman would want to go through this?

RECOGNISING EMPLOYERS’ CONCERNS

Bharati: Right now do you live with your parents still?

Wham: Yes, yes. I still live with my parents.

Bharati: And do you have a foreign domestic worker in the home?

Wham: Yes I still have a live-in domestic worker.

Bharati: How would you say you and your family treat your helper, as opposed to how many other Singaporeans might be treating theirs?

Wham: I’m always seen as the one who sides with the maid. That’s typically the impression even friends get, when they talk to me about their problems with their domestic workers. They say, “I know you’re their advocate, but I have to say this … ”

It’s sometimes challenging because when you’re dealing with close friends and family, it is not easy changing mindsets. And they have their concerns, and they have their issues, which I think has to be addressed. I think being able to consider their perspective helps me in my activism and my advocacy also.

Bharati: You recognise that employers’ issues need to be addressed too? For instance, they have good reasons for worrying their helpers may fall in with the wrong crowd if they are given the day off – things like that? You recognise these concerns are valid?

Wham: Yes, because a lot of it is structural. The problems and challenges that employers face can also be traced back to how laws and policies shape their behaviour.

POLICIES AND “STRUCTURAL ISSUES”

Bharati: What are these structural issues?

Wham: For instance, the security bond policy.

Bharati: The S$5,000.

Wham: That’s right. So MOM says that “if you fail to repatriate this worker or if the worker breaches work permit conditions, you run the risk of losing this security bond”.

Bharati: You’ve said that this makes the employer feel responsible for the worker to the point that the employer starts to feel a sense of “ownership”.

Wham: That’s right.

Bharati: But the bond protects workers in a way, ensuring that employers discharge their duties and take some responsibility for the worker. For instance, they have to pay their maids on time, or lose the bond. One could say there are good reasons for the security bond.

Wham: I think it is unnecessary because it places too much burden on employers. Why should they be responsible for the misdemeanors of their employees? If a migrant worker commits an offence, let the law deal with them. Employers shouldn’t be policing their actions and behaviour. If MOM is concerned that employers will not fulfill their obligations, we already have other legislation which penalises employers for not complying with them.We have legislation such as Employment of Foreign Manpower Act. Why do we still need the security bond?

Bharati: What other policies do you think need a re-look, not just to serve the worker, but the employers as well?

Wham: Well, I think if we look at say, employers who have care-giving responsibilities. We see a lot of domestic workers who come to us for help, who say that they work really long hours, sometimes even round the clock taking care of babies, children and especially the infirm elderly. But employers find it more affordable to hire live in domestic worker, than to engage a nursing home or home nursing help to take care of their elderly parents.

Bharati: But concerns of Singaporeans struggling in a high-cost environment need to be considered too.

Wham: I think alternative care arrangements have to be a lot more accessible and affordable.

Bharati: Through subsidies?

Wham: Yes.

Bharati: You’ll have to get tax-payers’ buy-in on this.

Wham: Yes. We’re seeing a situation where there will be more elderly, because the baby boomer generation is growing older. So I think tax-payers have to be willing to do this, to serve themselves when they get older too.

Bharati: Wouldn’t working on behalf of the employers to effect these changes serve your cause too?

Wham: Yes. I think employers do have their concerns. And that’s something that has to be looked into. But we are a workers’ group. So the workers and their priorities would be our main concerns. So I believe that employers should also lobby the Government and get their points and their issues across to them. But I think it would be a conflict of interest for one organisation to advocate for both.

But I think what employers also need to see is that when we advocate for workers, it also helps them. Because when domestic workers, or migrant workers have their rights, when they have days off, they have regulated working hours, they will also be more productive at work, they will also perform better.

Jolovan Wham speaking at a protest at Hong Lim Park (Photo: Dylan Loh)

So just because we advocate for workers’ rights, it doesn’t mean that it will be detrimental to employers, or that we are antagonistic towards employers. It’s important for employers, and also agencies, to reframe this issue and understand that when workers have rights, they benefit too.

And of course when the Government doesn’t legislate domestic work, put it under the Employment Act, then what you’re basically telling employers is “you have a free pass to work her around the clock”. And that’s not right.

Bharati: But the Government has valid reasons for this.

Wham: Well, they have official reasons for this. They say that each household is different, and different families have different needs. So it is not realistic or practical to legislate domestic work.

Bharati: You don’t see any validity in that?

Wham: I don’t. I mean, yes, true, different families have different needs. But if you look at any industry, every company also has different needs, different requirements. So the reason we have standards is so that we prevent abuse and exploitation from happening. Foreign domestic workers are employees too. And we sometimes forget that just because this woman is living in a house, it doesn’t mean that she’s at your beck and call 24 hours a day.

But it’s very tempting you see, because this person is living there. So she’s always at your disposal. So the way the employment arrangement is structured encourages exploitation and abuse.

Bharati: It’s not just about foreign domestic helpers. It’s about other foreign workers as well, who are working in construction, for instance. We’ve seen non-payment of salaries, inadequate medical care, inadequate living conditions, inadequate meals, racism, classism on the ground. What do you think has led to all of this?

Wham: Well, it’s a combination of our culture and social policies, which encourage these kinds of problems. This phenomenon is not unique to Singapore. Classism, racism, sexism, where there are human beings, these problems will exist. But I think what’s important then is that advocate groups like HOME, other NGOs activists, we take the lead to shape the discourse and raise awareness so that these kinds of negative social attributes will not be mainstream.

WE DON’T HAVE A CULTURE OF HUMAN RIGHTS

Bharati: You said it’s a combination of our culture and social policies. Expand on that.

Wham: Well, because in Singapore we don’t have a culture of human rights. We don’t have a culture that mainstreams human rights advocacy.

Bharati: A lot of people still see human rights as a Western concept.

Wham: Right. That’s because our leaders tell us that. That it is a Western concept. But that’s not true. People have been fighting for their rights for centuries, not just people in the West. But if you look at countries like China, India, many countries around the world over the centuries, there are still various rights violations in these countries, but they continue to fight for them. They don’t say it’s a Western concept. The quest for human liberation is something which is universal. So to say that this is a Western invention I think is a fallacy.

Bharati: You’ve been talking about these issues for many years, yet it seems very little has changed on the ground in regard to the treatment of migrant workers. Some may say you’ve failed to persuade the authorities and people on the ground.

Wham: These are not things that can change overnight, so it requires people not just to raise awareness but to also talk to policy-makers, Members of Parliament. We must take charge. And we must say that “this is important, and we want these changes to happen.”

I think an anti-discrimination legislation will definitely help set the tone. The Government’s approach so far has been to educate, they don’t think that legislation is effective. It’s better to educate rather than legislate. So I believe that education is important, but you need to have the tool. Education and legislation have to be part of the plan to tackle these issues.

Bharati: Before we talk about how you can encourage people to take charge, why do you think legislation is necessary, even in an environment where education may be comprehensive?

Wham: Because there will always be people who will not, who will be discriminatory, there will always be bigots out there. If you can get away with murder, you get away with murder right? So that’s what legislation is for.

Bharati: But right now, we have rules and guidelines already. People are violating these anyway. Enforcement can’t occur 100 per cent of the time. So don’t you think education will be more effective than legislation – people need to be able to do the right thing, and not just because they fear being caught, or think they can do the wrong thing and get away with it.

Wham: We’ll have to ask why people aren’t following these rules. Is it because implementation and enforcement is not effective? Is it because mechanisms for redress are not working? So I don’t think it is enough to just say that “Oh we have the rules but then, nobody’s following them so let’s not have rules.” I think we need to ask deeper questions about effectiveness and whether laws and policies are adequate.

“POLITICAL POWER” AND BUY-IN

Bharati: Why do think the Government is resisting legislation?

Wham: Because the reality is that migrant workers don’t have political power in this country. They don’t vote. And as a result of that, their concerns tend to be shoved to the bottom of the list. And this is inevitable, not just in Singapore. It happens everywhere around the world. The ones with the political power will be the ones who have the bigger voice. It’s also only natural for the Government to heed the concerns of their voters first, rather than the concerns of migrants, because that’s how the political system is set up.

I wouldn’t say that this is the Government’s fault, because this is what is happening all over the world. But what’s important then is that citizens ourselves must say that this is a concern for us, and this is our priority, then the Government will listen and do something about it.

Bharati: We’ve seen a lot people say “Yes, I care about this issue and that issue.” But once they know what the trade-offs are, they might rethink how they feel. For instance, if we are to treat migrant construction workers better, their working hours would be better, they would get paid better, but all of that may require citizens having to pay more for services. Citizens may have to pay more for their homes, because construction costs will go up due to higher labour costs. Citizens may have to wait longer for their homes and shopping malls to get ready because if we are to respect human rights, our migrant workers wouldn’t be working such long hours. To what extent do you think even the people who say “Yes, I do care about the migrant workers in this country,” are willing to actually stomach those tradeoffs?

Wham: I think it depends on what kind of society then you want to be right? So are we a society that only thinks about things in terms of dollars and cents and what’s more convenient for us?

Bharati: How are you going to convince people who lean that way to change their minds?

Wham: The problem is we need to have more information to decide what kinds of tradeoffs we want. I think there aren’t enough debates about whether if we give migrant workers more rights, would we actually really have to bear the costs of it, will it really be more inconvenient for us. So we haven’t really had these kinds of discussions yet. So far, the discussions on migrant labour have been just about how do we wean employers off migrant workers, how do we create an economy that uses less migrant labour and is more productive.

We tend to frame a lot of our discussions in this way, rather than talk about it in terms of their rights, and whether if we grant them rights, we will really be suffering for it. Because where are the facts and the figures and the statistics for that? We don’t really have empirical evidence to say that.

Bharati: Wouldn’t it be logical to expect that there will be tradeoffs and to wonder if Singaporeans can actually stomach those tradeoffs? For instance, even if we just talked about foreign domestic helpers, employers have said, “If I give them a day off, it would mean I don’t have a worker for a day. How will I cope?” Giving a person rights tends to be seen as being tantamount to inconvenience for the employer.

Wham: But how I would frame it is: Why would you want your domestic worker to be the one that’s constantly caring for your children or your parents? Don’t you want to develop a relationship with your own children or your own parents? Do you need a domestic worker so much to the extent that you can’t even let her off for one day in a week?

I understand that there are concerns about costs, there are concerns about inconveniences, but I think we also need to look at it from the perspective which I have mentioned just now, which is that if you give your domestic worker her rights, you let her go off every week, when she comes back on Monday, she works better for you. She’s not stressed out.

We’re seeing a lot of reports now of domestic workers either abusing the children under their charge or even murdering their employers and these domestic workers are diagnosed with mental health problems. So we need to ask ourselves if we don’t give them their rights, are we causing them to be stressed out at work? Are we causing these problems?

Bharati: This isn’t the only issue though. What about the tradeoffs in the other areas I mentioned earlier? How do you plan to convince people?

Wham: Until we actually do proper research. Until the Government discloses more figures and statistics about the migrant workforce here, it’ll be very difficult for us to draw these kinds of conclusions.

Bharati: Can’t you do the research? Why wait for the Government?

Wham: Certain things like how much is generated in terms of revenue from some of these streams need to be disclosed by the Government, what are the other priorities the Government wants to take into account, etc. So if I talk about it as an NGO, if I talk about it in terms of cost, the Government is already making it very costly for employers to hire migrant labor. For instance, levies now can be as high as S$1,000 per worker per month. The average levy that a construction company pays could be about S$500 to S$700 a month.

So why don’t we not have employers pay such high levies, and instead channel these costs that they’re paying to the Government, to the worker’s welfare? Because the Government’s intention is to discourage employers from hiring migrant workers, but instead of making it more costly by paying the Government in taxes, they should make it more costly in terms of ensuring that workers welfare and rights are respected. And I think this is actually consistent with their current policy framework.

But whenever we talk about rights and cost, I think what’s often not discussed is how the Government itself is making it costly for companies too. So why not get the levy out of the equation? I think when companies don’t have to pay levies, they would be more willing to invest in worker’s welfare.

Bharati: Considering how things have been going so far, do you think employers will really voluntarily invest in welfare, even if they didn’t have to pay high levies?

Wham: I think we have to understand that just because you give someone rights, it doesn’t mean that it will be a cost to you, because there is a social good that comes out of that. It also benefits individuals. It benefits employers. In my view, it benefits everyone. But if we continue to frame it as, “I give you rights, then I will suffer, then I will have a cost,” then we’re not properly framing the issue.

Bharati: As an activist, you have the power to re-frame the issues, but you don’t seem to have made much headway. Why?

Wham: We are trying and I think change takes time. These mindsets have existed here for so many years, so it will take time. For instance, women were clamoring for the right to vote for over a 100 years, and it was only finally legislated after such a long period of advocacy and campaigning. It took 100 years for them to get the right to vote.

So I think that any kind of social change that you want takes time. So you need to have the stomach and the endurance and the persistence, if you really want to see the change you envision materialise. And this is what keeps me and my colleagues going, because we know that the change can come and will come. And even if it doesn’t happen in our lifetime, we are starting a movement that our successors can build on. I think we cannot have a short-sighted view on social change.

Because if you look at history, it is something that takes generations. It has to start somewhere, and it just happens that we are the pioneers when it comes to migrant rights. And we hope that succeeding generations of people can capitalise and build on what we have achieved.

SUBSIDISING ACCOMODATION COSTS FOR “LIVE-OUT” MAIDS

Bharati: The Indonesian government recently said it will not allow its citizens to be live-in maids abroad. Do you think such rules should be applied across the board – to all FDWs from any country – by the Singapore authorities?

Wham: Yes, I think it should actually be an option. All FDWs should have the option to live-in or live-out. And I say this because we have done consultations with domestic workers. We’ve spoken to them. And some would prefer to live with their employers. And there are also some employers who would prefer domestic workers to live with them. But there are also other employers and other domestic workers who would rather they live out. So I think what’s important is to give people choices. The Government should make it optional.

Bharati: But wouldn’t it be better in terms of worker protection if FDWs didn’t live-in? Some of the abuse – working hours, freedom of movement – won’t occur if they lived outside the home.

Wham: Some domestic workers are protected even though they live with their employers. So just because you live with your employers doesn’t mean that you’re being exploited or abused. If the domestic worker does feel that she’s being abused and exploited because she lives with the employers, that’s where the option to live out should be given. So I don’t think just making it compulsory is necessarily the solution. But if it’s implemented, other things would have to change as well.

Bharati: Such as?

Wham: Like the right to switch employers freely, security bond requirements. These are things that will have to change so that, for instance, if my employer doesn’t allow me to live out, I should be able to switch employer freely to find someone who’s willing to let me live out. At the moment there isn’t that choice.

Bharati: What about the cost of accommodation and transport to and from work for FDWs who live outside the employer’s home? Who should bear these costs?

Wham: I think we need to build more of these kinds of dormitories and infrastructure to meet the demand for live-out domestic workers. I think it has to be affordable. But this also means that employers may have to pay for it and I don’t see anything wrong with employers actually paying more.

Bharati: The employers will see something wrong with it though.

Wham: Yes, but if you have options available, it may not be so bad. Employers should be provided with more affordable care options for their kids and elderly family members. I mentioned that earlier. So they don’t only have one option – a live-in domestic worker to take care of their elderly or their children. But I do also think that for the employers who can’t afford to pay more for the workers’ accommodation, the Government should come in with subsidies.

Bharati: Of course, Government’s money is tax-payers’ money. Many of the suggestions you’ve made would require an injection of this. For instance, more accommodation options for migrant workers, FDWs and subsidies for this to the employers, more affordable alternative care arrangements. There needs to be buy-in from the people.

Wham: And the Government is actually moving on this, building more nursing homes and they’re already starting to subsidise families who hire live-in domestic workers to care for the elderly. So I think it would be a natural progression in terms of social welfare expenditure if families who are struggling and cannot afford to provide live-out options for the domestic worker, are subsidised.

ENGAGING WITH THE GOVERNMENT

Bharati: You been described as being rather confrontational in your engagement with the Government.

Wham: The problem is that in Singapore we don’t have a culture that promotes, and even to a certain extent, accepts advocacy, which is actually the role of civil society. My challenge of course is being able to advocate effectively, but yet at the same time not alienate. I think we’re being able to achieve that balance.

And how we’ve been able to do it is because we run direct services as well. So we have a very good understanding of what’s happening on the ground. Workers come to us with their problems and their challenges, we collate this information and this data, and we are able to advocate effectively, because we have stats, the actual case studies and stories to back up our assertions and our claims.

Just because we have a view that’s different from the Government and we express it publicly, it doesn’t mean we can’t have a good working relationship. We do have a good working relationship. So I think this is something which we need to accept as the role of civil society.

Bharati: You said your challenge is being able to advocate effectively, yet not alienate the authorities. But the fact that you’ve been raising the same issues over and over again and things have not really changed could be interpreted as a failure on your part to effectively engage with the Government.

Wham: Well, the systemic problems are still there, but I have hope, because I have seen how some of our advocacy has had an impact. For instance, 10 years ago, when we talked about human trafficking, this was not really a problem Singapore society or even the Government wanted to accept.

But now we have a law that’s dedicated to combating human trafficking. And this is a result of advocacy. It’s because we came together and we said that this is an important issue that has to be tackled. And as a result of our advocacy, now we’re seeing greater and better protection for traffic victims.

I’m not saying that things are hunky-dory now. Of course not. There’s definitely a lot of room for improvement. But in the course of the work that I’ve been doing in the past 12 years, I have seen how we have achieved small victories. And these victories are significant, because it paves the way for us to win even bigger victories.

GETTING SINGAPOREANS TO BE EFFECTIVE ACTIVISTS

Bharati: You talked about how Singaporeans need to speak up about these issues so that the Government will take them more seriously. How do you plan to get more of us to take action – enough for the Government to sit up and take notice?

Wham: I don’t think Singaporeans are not concerned at all. The challenge is how do we translate this awareness into action that would lead to the change that we want to see. We need to encourage Singaporeans to speak up more, to initiate more projects that look into addressing these problems, and talk to their members of Parliament, and say that your Meet-the-People sessions shouldn’t just be about your own personal grouses.

Bharati: For many people, it is though.

Wham: Usually it is, yes exactly. But your MP is also supposed to represent issues which you care about, which may not necessarily be issues that impact on you directly. So I think we need to do more of that. I think it is getting Singaporeans more involved in speaking out, and being more involved in advocacy and campaigning. This is something that is very new. We’re not used to being advocates of issues that we care about.

Bharati: Why do you think that’s so – are people still afraid of expressing themselves?

Wham: Yes, the political culture has to change, but it’s going to be very difficult as long as the ruling party is dominant in Parliament. So that’s why it’s important that we support more political diversity in this country, and that we have more voices in Parliament. And this is when the political culture will change. But until that happens I think issues like self-censorship, issues like the lack of civil liberties in this country will remain the same.

Bharati: But in order for political culture to change, people need to want change. Based on the last election result, it’s possible the majority of Singaporeans don’t think we need more voices in Parliament, or think that the alternative voices were up to the mark. In order for political culture to change, people need to have a desire for it. So if that’s your desire, how will you convince others of this and of the need to speak up about issues beyond their own personal concerns, even today?

Wham: Yes, so I think other political parties need to do more, but on our part, the activists’ part, even though the ruling party controls a lot of our institutions, including our media, we need to point out that opportunities for alternative views to be expressed are there. So the Internet in the last few years, has really been quite an effective platform for other voices to be heard.

Bharati: But you need to get your voice heard effectively and people have been known to get into trouble for what they say online as well.

Wham: That’s true, that’s true. But I think if we compare it to say 10 or 15 years ago, there are a lot more things that are being said now, which we wouldn’t have dreamed would be said back then. So I think in that sense we have progressed.

Bharati: But whether or not that has an impact on the way the Government conducts itself is a totally different issue.

Wham: Right. I think if more people do it, if more people occupy that space, if more people come in to enlarge that space, then I think that will initiate the political and cultural change that we want to see. But as long as the space we are occupying is just the preserve of a small group of people, then it’ll always be a fringe activity.

Bharati: So how do you plan to get more Singaporeans to take effective action?

Wham: The tools are available, but what’s holding people back is the self-censorship. And it’s not an easy issue to tackle because self-censorship has been a feature in Singapore society for decades. So, for the kind of change to happen will really take time. But what I can say now is that for media practitioners who are outside of the establishment, for advocates, for activists, for concerned citizens, where there’s an opportunity to voice out, do it. Because change takes time.

ADVOCATING FREEDOM OF SPEECH

Bharati: Away from HOME, you are also a member of the Community Action Network. Some time ago, you were involved in a candlelight vigil to show support for protesters in Hong Kong. You’ve also spoken at Hong Lim Park about teenage blogger Amos Yee.

Jolovan Wham (centre) and participants shout slogans during a protest to free blogger Amos Yee at Hong Lim Park on Jul 5, 2015. (Photo: Reuters)

You’ve recently spoken up about the case involving Teo Soh Lung and Roy Ngerng. While you say you’re careful not to alienate the authorities in your migrant worker advocacy work, to what extent would you say in your advocacy of freedom of speech and expression, the pressure that you’re exacting may indeed alienate the authorities?

Wham: Right, this work is different. But we do everything legally. So I think as long as we keep within the confines of the law, then I don’t think I should be afraid, or I should hold back on my activism. Change will not happen if we hold back.

Bharati: You talk about doing things legally, but during one of your rallies, the foreigners who showed up did not have permits and you had to pay a fine because of this.

Wham: Hong Lim Park is an open space. So anyone can come. And it would have been impossible for me to distinguish who was a foreigner and who wasn’t. And this is why I feel like that the law needs to change, or it has to be tweaked at the very least. Because how does one prevent foreigners from coming into Hong Lim Park to participate? Do I check their IDs? But I don’t have the legal right to do that. So if somebody insists on participating an event at Hong Lim Park, what can I as the organiser do? I think these are the grey areas. And this is why I feel that it’s very difficult to allow protest, but at the same time, not allow foreigners to participate.

Bharati: How do you plan on making headway on such issues effectively without alienating the authorities?

Wham: Well I think even though the freedom that’s given is limited and I disagree with the rules. But at the same time I wouldn’t take the view that just because I’ve only been given this space, I will not use it at all because it goes against my principals. Because like I said, change is something that takes time, and protest culture is also something that is very alien to Singaporeans.

Bharati: In a nation where most people are probably just concerned with whether the economy is working, will they have a job, a home tomorrow, in a nation where many seem to be more concerned about utilitarian issues, why do you think what we have been speaking about today is so important?

Wham: Well that’s because whether you have a home tomorrow, whether the economy will be working tomorrow, is also tied to our right to free expression, our right to information. It’s also tied to democracy. So these are not mutually exclusive contexts. We all have a stake in what Singapore should be, the kind of country we envision for our future. And how I envision it is a country that upholds principles of social justice, and treats everyone equally and fairly.

– CNA/av

View all posts in Anisya Blog

Posted on 20 Jun 2016

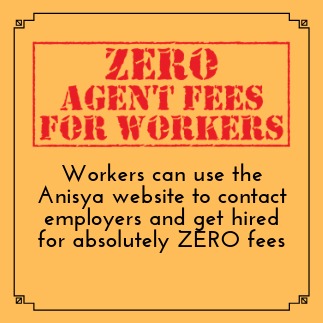

Help FDWs avoid debt

Anisya can help with the MOM paperwork

Found a suitable worker on Anisya? We can help with the MOM paperwork. Our service fee is $450. Click here for more info.

Full service hiring available

Need to hire an FDW in a hurry? Let Anisya help you with screening, short-listing and scheduling interviews with workers, and managing all the MOM paperwork formalities! More details here.

Anisya Web Services works in partnership with Anisya LLP (MOM License 12C5866) for MOM related transactions.

Anisya is a proud Social Enterprise member of the Singapore Centre for Social Enterprise (raiSE) and the Business For Good community which promotes the use of business for social impact.