17% of Hong Kong’s Domestic Workers Are Engaged in Forced Labor, Study Says

17% of Hong Kong’s Domestic Workers Are Engaged in Forced Labor, Study Says

The plight of domestic workers in Hong Kong has made headlines in recent years after several high-profile cases in which employers had beat and tortured their helpers.

A new study shows that, far from being isolated cases, instances of abuse are more routine and widespread than previously suspected.

A Justice Centre survey of more than 1,000 domestic workers found that 17% were engaged in forced labor. That means there could be more than 50,000 domestic workers working under duress among Hong Kong’s population of about 336,000 domestic workers, the vast majority of whom are women from Indonesia and the Philippines.

Among those engaged in forced labor, 14% had been trafficked into it, the survey found.

Domestic workers are tightly woven into the fabric of Hong Kong society, providing the affordable childcare and elderly care that allow parents to work. One in every three households with children employs a helper. Without private spaces of their own, domestic workers flood the city’s parks and sidewalks on Sundays to chat, sing and practice their religion sitting on cardboard boxes or plastic tablecloths.

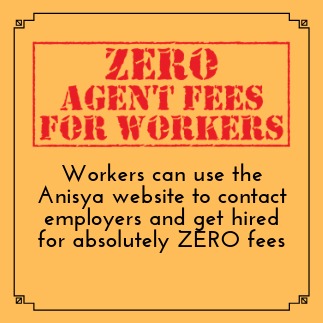

The most significant predictor of forced labor is whether or not a worker has debt, says Justice Center. Even before a woman starts work as a domestic helper in Hong Kong, she faces a raft of fees: training, recruitment, placement, medical examinations, insurance, certificates, visas and passport fees. Most of these are paid via loans.

More than 35% of respondents had debt burdens equal or greater than 30% of their annual income. Those who secured their jobs at home took on average 7 months to pay off their debts. This locks them into potentially abusive households.

Take the case of Amalia, a 28-year-old Indonesian woman profiled by Justice Centre. Amalia took out a loan to cover her recruitment costs, which totaled US$2,007 (HK$15,576) and was required to attend a training facility in Indonesia, where her passport was confiscated. In Hong Kong, Amalia works 14 hours a day and is given one day off every three weeks. She is paid US$517 (HK$4,010) a month and sends 50% of her salary back to her family in rural Indonesia. Her employment agency has said she can’t quit until she has repaid her debt.

Justice Center classifies unfree recruitment, work and life under duress and the impossibility of leaving as examples of forced labor. This includes workers being locked in training facilities or being required to work 20 hours a day, in the middle of the night, and on the legally mandated one day off. The International Labour Organization defines forced labor as work done involuntarily or under the menace of any penalty.

To be sure, many domestic workers are happy in their working situations, said Justice Center. The majority of women move voluntarily to seek a better life for themselves and their family in a city where they can earn relatively more money. Yet the lack of enforcement and “scattered” legislation in Hong Kong heighten the chances of exploitation and abuse, it adds.

Hong Kong mandates domestic workers have one day of 24 hours off a week, 12 holidays a year, a food allowance and be paid a minimum wage.

Yet those rules are hardly enforced, the study found. The survey found that domestic workers on average work 11.9 hours a day and that 36.7% have to work some portion of their mandated 24-hours off. Close to 72% were paid less than the minimum wage of $529.58 (HK$4,110) a month. Nearly 40% do not have their own room and 35.2% share a room with a child or elder person.

More than half of domestic workers surveyed, 55%, said they did not feel free to quit their jobs because they believed all jobs had similar living conditions. And more than 66% of those surveyed demonstrated strong signs of exploitation but not enough to be classified as forced labor. Only 5.4% showed no signs of exploitation.

In Hong Kong, foreign domestic workers also face onerous regulations such as a requirement they must live with the family for whom they work. A worker who wants to terminate her contract has two weeks to find another job in Hong Kong before being deported. And a worker who files an abuse charge against an employer is prohibited from working unless the case is resolved. They are also not entitled to rights to become a permanent resident of Hong Kong after seven years, as other foreign workers are.

Advocates have repeatedly lobbied for the live-in rule to be scrapped, as it traps workers with potentially abusive bosses. A spokesperson for Hong Kong’s Labour Department told China Real Time the live-in requirement must be “strictly maintained,” citing the need to give employment priority to local, non-foreign domestic workers, and the potential rise in medical, private housing and public transportation costs if workers are allowed to live elsewhere.

In 2014, Erwiana Sulistyaningsih, a former domestic worker, was beaten and tortured by her employer for months before she escaped to Indonesia. The employer was sentenced to six years in prison. Previously, a Hong Kong couple were sentenced to prison for whipping and scalding their helper with a hot iron.

Like many other advocacy organizations, Justice Centre recommends scrapping the live-in and two-week limit requirements, as well as stricter laws to prohibit forced labor and give government departments the power to identify and assist victims. The center says its findings show that cases such as Erwiana’s aren’t an example of a “bad apple” employer, but a “tip-of-the-iceberg” scenario.

–Anjie Zheng. Follow her on Twitter @anjiezheng.

View all posts in Anisya Blog

Posted on 15 Mar 2016

Help FDWs avoid debt

Anisya can help with the MOM paperwork

Found a suitable worker on Anisya? We can help with the MOM paperwork. Our service fee is $450. Click here for more info.

Full service hiring available

Need to hire an FDW in a hurry? Let Anisya help you with screening, short-listing and scheduling interviews with workers, and managing all the MOM paperwork formalities! More details here.

Anisya Web Services works in partnership with Anisya LLP (MOM License 12C5866) for MOM related transactions.

Anisya is a proud Social Enterprise member of the Singapore Centre for Social Enterprise (raiSE) and the Business For Good community which promotes the use of business for social impact.