Day in the life of a migrant worker in Singapore

In the first installment of a two-part series, photojounalist Kate Hodal captures the life of an out-of-work Bangladeshi worker and a domestic helper from the Philippines

By Kate Hodal 19 July, 2011

What keeps Singapore running like a well-oiled machine?

The housekeepers, construction workers, dock workers, gardeners, street cleaners and countless other migrant workers who call Singapore home.

Often invisible to the average eye. I sought to capture fragments of their experiences here, snapshots into their daily lives, by asking them what just one day is like in their shoes.

Mirroring the individuality of their experiences here, I shot each of the interviewees with a different camera, with the results somewhat of a “gamble” — a word many of my interviewees used to describe their own experience here in Singapore.

This is the first of a two-part series.

Davy, 41, domestic worker from the Philippines

One in six homes in Singapore has domestic help, according to recent government figures, with Filipinas comprising around one-third of the 201,000 domestic workers who call the Little Red Dot home.

Davy, 41, from Ilo Ilo, Philippines, came to Singapore 16 years ago and has seen many of the city-state’s changes at first hand.

From 7 a.m. until 10 p.m. Monday to Saturday, Davy, cooks, cleans and gardens for her employers, for whom she has been working for the past 16 years.

But her “real” work lasts from 10 p.m. until 1 a.m., and all day Sunday, when she serves as a de facto counsellor to domestic workers of any nationality, for free.

“Sometimes they’re pregnant or don’t have enough food or haven’t slept enough or don’t get any days off,” says Davy. “I listen to their problems and sometimes refer them to a shelter if they really want to run away.”

“For the pregnant ones, I always tell them, ‘If you want to make yourself happy by playing around, then be safe — use contraceptives.'”

“At the end of the day, we all have desires, but I’ve turned mine outwards to helping others, so I don’t get frustrated with my life here.”

“Singapore wasn’t at all like what I expected,” explains mother-of-two Davy, who left behind her job as a legal secretary, as well as her 11-month-old daughter and five-year-old son, to the care of her husband and mother in 1995.

“I was only 25. I was so scared, I didn’t have any time off and I didn’t know what to do when I did. So I started reading to pass the time.”

Often spending hours at a time at Borders Bookstore in Wheelock Place, Davy figures she’s read 3,000-odd books in the last 16 years — ranging from Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” to crime thrillers by Patricia Cornwall.

Now, she has her own plans as an author: “Our stories as domestic workers are very colorful, and they need to be told.”

Remittance centres in the many malls of Singapore, like the one Davy frequents in Lucky Plaza, are at their busiest at the weekends, when many of the migrant workers who are allowed a day off send money home.

Davy sends 70 percent of her S$550 per month salary home to the Philippines every month, a budget which has allowed her to send each of her six siblings, as well as her two children (now aged 14 and 19) to school and college.

“My greatest achievement was when my youngest brother graduated as an accountant,” Davy says. “Now he works at the biggest accounting firm in Manila. I tell him, ‘Now you earn good money, you have to save it for when your sisters’ kids go to college. They need you.'”

Every other Sunday of the month, Davy runs Enrichment Programme workshops at a local charity called Transient Workers Count Too (www.twc2.org.sg), where she teaches other migrant workers basic computer skills.

“Many migrant workers don’t know that basic computer programmes — like Yahoo Messenger, Facebook and Skype — can help them stay connected for free to family members back home,” she says. “It’s much better than relying on the phone, and it helps us, as workers, feel like we’re learning valuable skills for ourselves.”

“I like learning new things, it keeps me alive,” says Davy, in between choreography sessions, at a new bi-monthly Sunday hip-hop class, which is partially sponsored by local charity Migrant Voices (www.migrantvoices.org).

“I tell my kids about my hip-hop class and they laugh at me. I talk to them every day, we tell each other everything, because when I see them at the end of every two-year contract, I am shocked.”

“They grow up so fast, the way they dress, think and communicate. They actually told me not to buy them anything anymore, because they said I always get it wrong.”

“So sad, lah! But that’s life. When I move back to live there again, maybe in a couple of years, I think things will be different.”

Photographs were shot with a Sony A-290.

Turn to page 2 to read about Shafiqul, a 36-year-old, out-of-work Bangladeshi worker.

Shafiqul, 36, out-of-work construction worker from Bangladesh

Of the roughly 1.25 million migrant workers here on special employment passes, there are no official figures for the number out of work due to medical or legal problems.

But some 2,500 workers sought assistance for these very reasons from workers’ rights charities HOME and Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2), from 2006 to 2010.

Former construction worker Shafiqul, 36, from Bangladesh, is currently seeking damages for an accident he incurred at work in 2010.

A former factory worker in Dhaka, Shafiqul looks over his doctor’s notes: the Bangladeshi native has been unemployed and unemployable for the past 18 months, after a wall that he was tearing down on a building site toppled him onto the ground.

His left shoulder was dislocated, his elbow torn open, and his spine twisted under the weight of the rubble.

After being treated for his injuries at Singapore General Hospital (SGH), Shafiqul was surprised to find his former boss — along with “three Tamil gangsters” — looking for him at midnight at his dormitory.

“They come to chase me away back to Bangladesh,” Shafiqul explained to me in May. Such scare tactics are a fairly common occurrence for many migrant workers in Singapore, according to charity TWC2.

Unemployed and unable to pay rent, Shafiqul began sleeping in MRT stations and doorways around Farrer Park. He is now awaiting medical compensation from his former employer, via a manpower ministry-appointed lawyer.

Shafiqul’s first spinal operation was in December 2010, six months after his initial injury on the job.

This June, Shafiqul was readmitted to SGH for a second surgery, this one to fuse together two of his lower discs. Here, according to the inclinometer prior to the surgery, Shafiqul’s spine operates at 30 to 60 percent less than average.

Shafiqul’s surgery lasted four hours and bonded together two of his lower discs with a metal rod. His surgery — estimated at S$30,000 — is being paid for by his former employer, with whom Shafiqul is in both legal and medical dispute.

One SGH staff member, speaking anonymously, said she she can admit around 10 to 15 migrant worker patients a day, many of them with “dodgy paperwork” issued by their former employers.

Here, Shafiqul, who regularly sent money home to provide for his parents, siblings and new wife, does physical therapy exercises after the insertion of a 10-centimeter metal rod in his lower spine.

“What work I find now? I cannot carry more than five kilos, doctor say, for the rest of my life,” says Shafiqul. “One person problem is now come to seven person problem. I want to go back home and start again.”

As of the publication of these photographs, Shafiqul is still in hospital post-surgery. The photographs were shot with a Holga using 35mm film.

The second part of this series will be published on CNNGo on Thursday July 21.

A selection of the “A Day in the Life” photographs will be on display at the Goodman Arts Centre (90 Goodman Road, tel +65 63469400) from July 16 to 23, as part of the City Limits Gallery project. Go to facebook for more information.

Freelance photojournalist Kate Hodal has filed copy from steaming volcanoes in Iceland, the Prime Minister’s office in Tuvalu and the deforested jungles of the Amazon. When she’s not behind the lens or in front of the screen, she can be found madly dashing away on those other keys — the piano’s — or singing along with the buskers on Orchard Road.

Read more about Kate Hodal

View all posts in Anisya Blog

Posted on 8 Dec 2012

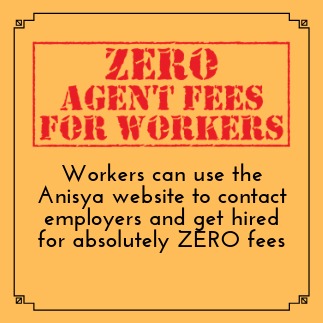

Help FDWs avoid debt

Anisya can help with the MOM paperwork

Found a suitable worker on Anisya? We can help with the MOM paperwork. Our service fee is $450. Click here for more info.

Full service hiring available

Need to hire an FDW in a hurry? Let Anisya help you with screening, short-listing and scheduling interviews with workers, and managing all the MOM paperwork formalities! More details here.

Anisya Web Services works in partnership with Anisya LLP (MOM License 12C5866) for MOM related transactions.

Anisya is a proud Social Enterprise member of the Singapore Centre for Social Enterprise (raiSE) and the Business For Good community which promotes the use of business for social impact.